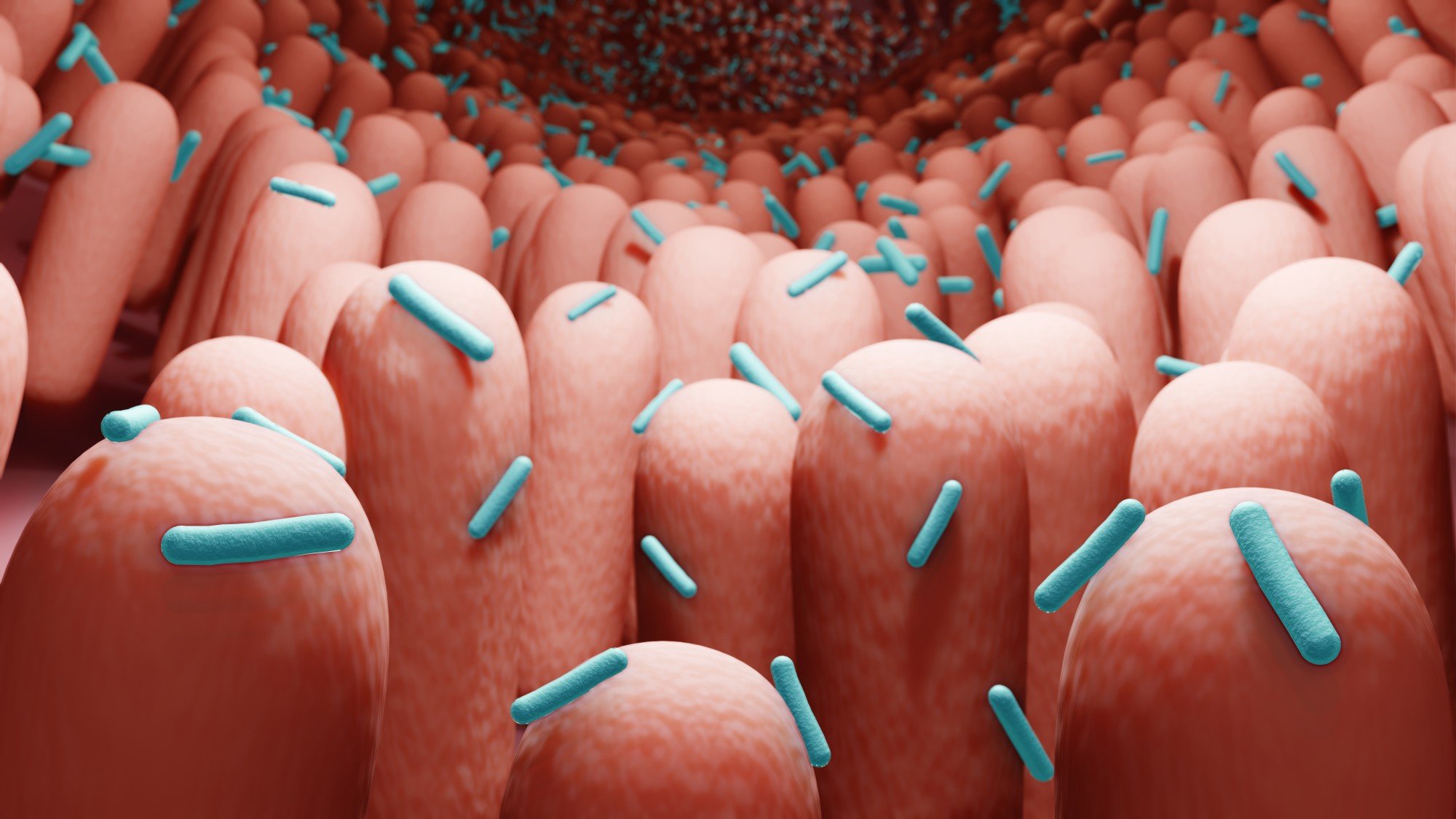

- Our gut health has a direct impact on our immune system function and overall well-being. Diet is a major factor in the health of our gut, or gut microbiome

- Eating foods high in fibre helps good gut bacteria thrive and produce nutrients and short-chain fatty acids that regulate blood sugar and reduce inflammation

Our gut health has a direct impact on our immune system function and overall well-being, and a plant-based diet can enhance it. Photo: Getty Images

Looking after our gut health is important.

Colorectal is the third most common cancer in men and the second most common in women worldwide. In Hong Kong it is the second most common cancer and accounted for nearly one in six new cancer cases in 2019, according to the Centre for Health Protection.

When doctors talk about gut health, they often use the term “gut microbiome”, a reference to the trillions of bacteria, single-celled organisms known as archaea and protozoa, viruses, fungi and yeasts that mostly reside in our large intestine.

These microorganisms begin colonising our gut at birth. Some are beneficial to the body, but our gut also houses “bad” or “unfriendly” microorganisms that can have adverse effects on health.

Our gut health has a direct impact on our immune system function and therefore our overall well-being, says Dr Andrew Wong Tin-yau, honorary consultant and specialist in infectious disease at Matilda International Hospital in Hong Kong.

“Dietary fibre is important for gut health, even though the human body cannot digest it. Instead, the fibre we consume passes relatively intact through our digestive system. As it does so, the bacteria in our gut feed on it, producing nutrients in the process. These nutrients, which include vitamin K, help support our immune system,” Wong says.

Infectious disease specialist Dr Andrew Wong Tin-yau says that our gut health directly affects our immune function.

Eating meals that are high in fibre also increases our microbiome’s production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as acetate, butyrate and propionate.

“These are chemicals that provide a vital energy source to our bowel lining, control our appetite, regulate our blood sugar and reduce chronic inflammation,” says Dr Alan Desmond, a UK-based gastroenterologist and general physician. “They even stimulate the production of serotonin and other hormones, which can influence our concentration, emotions and stress responses.”

What we eat plays a major role in shaping our gut microbiome and helping our good gut bacteria to thrive.

“In countries that eat a standard Western diet – one that depends on meat, dairy and processed foods for most of its calories – digestive health problems are extremely common,” says Desmond, who is also the author of The Plant-Based Diet Revolution.

“These range from conditions that negatively affect our quality of life, such as acid heartburn, irritable bowel syndrome and constipation, to diseases that can become life-threatening, like colorectal cancer and Crohn’s disease.”

Our gut bacteria thrive on fibre, found exclusively in plant foods, says Dr Alan Desmond, a UK-based gastroenterologist and general physician.

On the other hand, people who eat a high-fibre, plant-based diet tend to have a healthy gut microbiome and a lower risk of developing serious digestive problems. They’re also more likely to have regular bowel movements.

Probiotic supplements are often thought to benefit our health because they supposedly add more good bacteria to our gut.

Wong says that if you’ve been taking antibiotics for a prolonged period to treat or prevent an infection, probiotic supplements may help replenish the good bacteria in your gut.

“However, we still need more evidence that shows the benefits of probiotic supplements,” he adds. “Some studies have found that probiotics don’t colonise the gut at all and are in fact expelled by the body. The best way to help your gut bacteria is to eat plenty of fibre-rich foods.”

Prebiotics, also known as food for our gut bacteria, can be found in fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kimchi and natto. While these can help our gut bacteria to thrive, Desmond says that they should not be regarded as an essential component of a healthy diet.

There are a few ways to maintain the health of your gut microbiome:

Eat a wide variety of plant foods to feed your diverse gut bacteria. Photo: Shutterstock

1. Eat a variety of plant foods

Plant foods contain fibre, which our good bacteria love. Wong says that the average person needs more than 30 grams (1 oz) of dietary fibre per day, but most of us don’t eat even close to that amount.

As we have a diversity of gut bacteria, it’s important to consume a wide variety of plant foods. “Every plant-based food, be it a bean, green or whole grain, contains different types of fibre and important phytonutrients, and our microbiome loves them all,” says Desmond. “Keep count of how many different fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, legumes and spices you eat. Aim for more than 30 different plants per week.”

If eating beans, legumes and cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cabbage makes you gassy and bloated, be patient. These problems aren’t uncommon, and in fact, they’re likely a consequence of your gut bacteria not being used to digesting something so healthy.

Althea Tan Hutchinson is a founding partner of the Happy Plantarian, a whole food plant-based cooking school and nutrition consultancy in Hong Kong.

“It takes time for your digestive system to adapt to these foods, so try to persist,” says Althea Tan Hutchinson, a founding partner of the Happy Plantarian, a whole food plant-based cooking school and nutrition consultancy in Hong Kong. “Once you’ve established a somewhat optimal gut microbiome, the problems should alleviate.”

Soaking dried beans and legumes overnight before cooking helps break down some of their hard-to-digest starches, making them easier on your digestive system. Adding kombu (a type of seaweed) to the soaking water may also help make the beans more digestible.

Cruciferous vegetables contain sulphur-rich compounds that can cause gas. To counter this, Tan Hutchinson says not to eat them raw. She suggests finely chopping or shredding them before steaming, blanching or sautéing.

Adding ginger and turmeric to these foods can also help with gas and bloating, as these spices aid digestion.

Our gut microbiome helps control intestinal digestion. Antibiotics alter the balance and diversity of the microbiome.

2. Avoid unnecessary antibiotics

While antibiotics help us fight bacterial infections, Desmond says that if you have a cough or cold that your doctor believes will settle without antibiotics then take their advice. A single course of antibiotics seriously alters the balance and diversity of our gut microbiome.

“Another way to avoid excess antibiotics is to remove meat and dairy from your diet,” he adds. “Most antibiotics used in the world are given to farmed animals. These antibiotics remain in the food chain and affect our microbiome.”

Seven to eight hours of good sleep make for a healthy gut. Photo: Getty Images

3. Get sufficient sleep

“Our gut bacteria seem to work on the same 24-hour daily cycle as the rest of our body,” says Desmond. “Some researchers even believe that our microbiome plays an important role in setting our body clock.”

Sleep deprivation, jet lag and shift work have all been linked to reduced microbial diversity. Look after your microbiome by getting seven to eight hours of quality sleep every night.

Regular exercise boosts our levels of healthy, fibre-loving bacteria and increase its diversity. Photo: Getty Images

4. Exercise regularly

According to Desmond, regular exercise boosts our levels of healthy, fibre-loving bacteria. In fact, in 2014, Irish researchers found that elite rugby players displayed an impressive level of microbiome diversity.

The World Health Organisation recommends 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week; 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity; or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week.

5. Spend time outdoors

“A sanitised indoor lifestyle isn’t ideal for our microbial health,” says Desmond. “We know that people who live in rural areas tend to have healthier and more diverse microbiomes than city dwellers. If you don’t live in the countryside, spending time in parks and gardens can help.”

Excerpted from South China Morning Post 7 Feb 2022