| Dr Andrew Tin-Yau Wong |

| Specialist in Infectious Disease Hong Kong |

Presentation and investigations

A 54-year-old male hepatitis B carrier was admitted to a private hospital. He was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis >10 years ago and was prescribed entecavir at the time. He underwent liver transplantation in 2008 and subsequently started treatment with tacrolimus, steroids, and immunosuppressants. Ten years after his transplant, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma – a post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease – with no bone marrow involvement and was given chemotherapy. During this time, his records showed a history of neutropenic fever.

About 1 year ago, the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes zoster with involvement of several dermatomes on his left lumbar and sacrum. He was admitted to hospital for fever and diarrhoea, but his blood tests were negative and chest X-ray did not reveal any markers of pneumonia. The patient was started on a course of levofloxacin, but was re-admitted 3 days later for shock and blood loss. His blood pressure dropped to 90/50 mm Hg, with tachycardia (110 bpm) and a haemoglobin level of 5.5 g/dL.

At this point, endoscopies and small bowel angiogram were carried out, revealing small intestine angiodysplasia and bleeding. Following laparotomy to correct angiodysplasia, the patient developed pneumonia, with Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from his sputum. His E. coli was shown to be extendedspectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)– positive, whereas his P. aeruginosa was resistant to amoxicillin, imipenem and levofloxacin.

Treatment and response

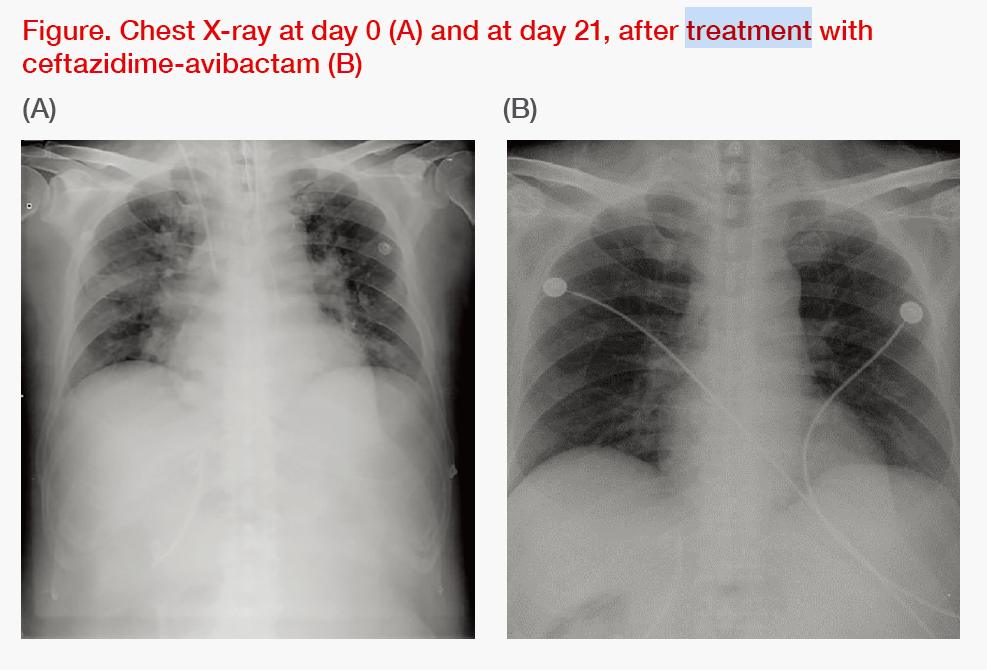

Initially, the patient was treated with vancomycin and meropenem. However, upon discovering that his P. aeruginosa was resistant to the latter, he was switched to ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA) at a standard intravenous dose of 2 g/ 0.5 g every 8 hours, which was given in combination with an aminoglycoside, amikacin, for 10 days. Overall, the patient responded well to treatment, with pneumonia resolving, as demonstrated by chest X-ray, and his vital signs stabilizing. (Figure) He has since been discharged.

Discussion

In Hong Kong, the strategy for pneumonia management depends on whether the disease is acquired in the community or at the hospital. For community-acquired pneumonia, a combination of a β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitor with a macrolide or a tetracycline is a common choice.

For hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), such as our patient’s, agents that could address the possibility of P. aeruginosa infections are typically used. As ESBL prevalence in Hong Kong is estimated at >20 percent, drugs against ESBL-positive infections, such as CZA, could be used as a carbapenem-sparing agent, preserving the utility of carbapenem.1

According to the results of a real-world, multicentre, retrospective cohort study, CZA is a viable option for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), which has become more common in Hong Kong’s public hospitals in the last 5 years.2,3 The same study demonstrated that receipt of CZA within 48 hours of infection onset was protective (adjusted odds ratio, 0.409).2 Furthermore, a recent literature review identified CZA as the best drug available for treating KPC and OXA-48 CRE.4

When selecting a second-line treatment for this patient, a combination strategy of CZA and amikacin was chosen due to multidrug resistance and at least two pathogens, E. coli and P. aeruginosa, contributing to his HAP. While an older antibiotic, colistin, could also be used, its toxicity profile, particularly hepatotoxicity, made it unsuitable for this patient with hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis. Other concerns associated with colistin include limited efficacy, dosing uncertainties and resistance.5

In addition, CRACKLE (Consortium on Resistance Against Carbapenems in Klebsiella and other Enterobacteriaceae), a prospective, multicentre, observational study, has provided evidence on the advantage of using CZA vs colistin in terms of Use of a β-lactam antibiotic/β-lactamase inhibitor combination in a patient with multidrugresistant pneumonia and multiple comorbidities Dr Andrew Tin-Yau Wong Specialist in Infectious Disease Hong Kong CASE STUDY 15 DOCTOR | DECEMBER ISSUE all-cause hospital mortality rate at day 30 after treatment initiation in patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae CRE infections (9 percent vs 32 percent; p=0.001).5 Furthermore, in an analysis of disposition at 30 days, patients treated with CZA had a 64 percent probability of a better outcome vs patients on colistin (95 percent confidence interval, 57 to 71).5

In addition to HAP, CZA can be used for managing complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections.6 In patients at high risk of severe disease, CZA can be used in the first line, but caution should be exercised in prescribing to preserve CZA’s usefulness, as first-line use may eventually lead to resistance.

| “According to a real- world study, CZA is a viable option for CRE, which has become more common in Hong Kong’s public hospitals in the last 5 years” |

While our patient responded well to CZA 2 g/0.5 g every 8 hours with no major side effects, it is important to continuously monitor the liver and renal function of patients on CZA and to implement appropriate dose adjustments, if needed. In patients with impaired renal function, normal dosage should be adjusted according to creatinine clearance (CrCL): for those with CrCL of 31–50 mL/min, the dosage should be adjusted to 1 g/0.25 g every 8 hours, while for a CrCL of 16–30 mL/min, the dose should be reduced to 0.75 g/0.1875 g every 12 hours.

CZA is contraindicated in patients who are hypersensitive to cephalosporins and show immediate and severe hypersensitivity to any other type of β-lactam antibiotics.6

Multidrug resistance in Hong Kong

Hong Kong has faced an increase in multidrug resistance in recent years. A 2013 study on transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) within 40 long-term care facilities (LTCF) in Hong Kong revealed that 21.6 percent of LCTF residents were MRSA-positive. 7 A 2018 study in 1,028 residents in residential care homes revealed MRSA prevalence of 30.1 percent and a prevalence of 0.6 percent for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter. 8 These findings are of particular concern, given the increasing number of elderly persons in Hong Kong requiring institutional care and frequent hospitalizations.7

While new drugs help to stay ahead of antibacterial resistance, physicians must exercise caution and attempt to conserve antibiotics wherever possible. Continuous improvement of infection control measures to minimize transmission rates in clinical practice remains important. Time is of essence when treating patients with multidrug resistance, as bacteria can multiply rapidly, leading to exacerbation and, in some cases, death.

CZA administered in a timely manner is a useful addition to the currently available carbapenems, particularly for patients with Gram-negative, multidrug-resistant infections in areas where ESBL is common.

References:

- J Med Microbiol 2014;63:878-883.

- Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz522.

- Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:24.

- Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;31:587-593.

- Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:163-171.

- ZAVICEFTA full prescribing information,

October 2018. - BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:205.

- Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:350-360.

Forward from《MIMS Doctor》