Editorial

Dr Andrew Tin-yau WONG

MBBS(HK), MPH (Johns Hopkins), MSc Infect Disease, LSTMH

(Lond), Dip G-U M (LAS), DTM&H (Lond), PGDipClinDermat

(QMUL), FRCP (Lond), FRCP (Edin), FFPHM (UK), FHKCP,

FHKAM(Med)

Specialist in Infectious Disease

Hon. Consultant, Infectious Disease Centre & Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital

MBBS(HK), MPH (Johns Hopkins), MSc Infect Disease, LSTMH

(Lond), Dip G-U M (LAS), DTM&H (Lond), PGDipClinDermat

(QMUL), FRCP (Lond), FRCP (Edin), FFPHM (UK), FHKCP,

FHKAM(Med)

Editor Dr Andrew Tin-yau WONG

When I got invited to be the guest editor for this issue last year, I decided to focus on viral diseases as this is an area where there are ever-changing developments in diagnosis and management and also vast public health implications. It was last year that I chose to dedicate the theme for this issue to be on ‘Viral diseases of global importance’ and started to approach authors. Little did I know that the COVID-19 would emerge as a pandemic with unprecedented devastation globally just a few months later!

In this issue, we are excited that Dr Jacky Chan and Dr Owen Tsang have kindly shared their precious experience and perspectives on COVID-19 therapeutics amid their extremely busy schedule while fighting with COVID-19 at the most frontline position. They have put in huge efforts in summarising the state-of-the-art management options for COVID-19.

Viral hepatitis B and C are two other viruses associated with significant morbidity and mortality. To this end, the World Health Assembly in 2016 adopted Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016-2021, which outlined a global goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030. The Centre for Health Protection has set up a Viral Hepatitis Control Office to formulate local strategies and an action plan. A Steering Committee on Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis was set up. Dr Rebecca Lam, the Consultant in charge of the Office, details the comprehensive local action plan and its implementation in the article ‘Elimination of Hepatitis B and C in Hong Kong’. Focusing on mother-to-child-transmission of hepatitis B, an antiviral Tenofovir has been recommended to be added to existing hepatitis B vaccine and immunoglobulin program to further reduce the transmission rate from hepatitis B carrier mothers to their babies. Dr Wing-cheong Leung will explain the rationale behind and its implementation in Hong Kong in the article entitled ‘Use of Tenofovir in further prevention of mother-to childtransmission(MTCT) of hepatitis B virus (HBV)’.

Apart from hepatitis B and C viruses, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is another important yet largely ignored virus with high cancer-causing potential at various anogenital and oropharyngeal sites. It is the commonest sexually transmitted diseases and is acquired very soon after sexual debut. Although HPV vaccine is useful in preventing the infection, the exposed and unvaccinated population are prone to the carcinogenic sequelae of HPV infection. Anal cancer is on the increasing trend worldwide in the past three decades. It is actually more common in women than men, especially in women with previous genital HPV infection or precancer/ cancer. In people who are infected with HIV, another important pandemic virus of the last century, HPV behaves more aggressively, and the risk of AIN is at least 30 times more than the general population! In the article ‘High Resolution Anoscopy for the management of HPV-associated Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia ’, I shall explain the rationale for screening in high-risk populations and on the use of HRA.

For the lifestyle section, originally I have invited my friend from the UK, who is a doctor, to share his wisdom on ways to enhance resilience among healthcare workers in the context of high work stress and burnout rate. Unfortunately, my friend came down with COVID-19 and had to take time for rest for a full recovery. He would be pleased to share with us in another issue when the opportunity arises. In the urge of time, I have decided to share one of my hobbies, sound therapy, and written an article in collaboration with one of my teachers and friends, Anthony Nec from the UK.

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to all the contributing authors for their time and great effort. I would like to thank Mr KM Ho, who has contributed a fabulous cover photo with a meaningful caption. I would also like to acknowledge my clinical partner, Dr John Simon, for providing useful feedback on selected articles. Last but not least, I would like to thank the editorial team of FMSHK for assembling this memorable issue on infectious diseases for us. I hope you enjoy reading this issue and any feedback is welcome!

| Published by The Federation of Medical Societies of Hong Kong |

| EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dr CHAN Chun-kwong, Jane 陳真光醫生 EDITORS Prof CHAN Chi-fung, Godfrey 陳志峰教授 (Paediatrics) Dr CHAN Chi-kuen 陳志權醫生 (Gastroenterology & Hepatology) Dr KING Wing-keung, Walter 金永強醫生 (Plastic Surgery) Dr LO See-kit, Raymond 勞思傑醫生 (Geriatric Medicine) EDITORIAL BOARD Dr AU Wing-yan, Thomas 區永仁醫生 (Haematology and Haematological Oncology) Dr CHAK Wai-kwong 翟偉光醫生 (Paediatrics) Dr CHAN Hau-ngai, Kingsley 陳厚毅醫生 (Dermatology & Venereology) Dr CHAN, Norman 陳諾醫生 (Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism) Dr CHEUNG Fuk-chi, Eric 張復熾醫生 (Psychiatry) Dr CHIANG Chung-seung 蔣忠想醫生 (Cardiology) Prof CHIM Chor-sang, James 詹楚生教授 (Haematology and Haematological Oncology) Dr CHONG Lai-yin 莊禮賢醫生 (Dermatology & Venereology) Dr CHUNG Chi-chiu, Cliff 鍾志超醫生 (General Surgery) Dr FONG To-sang, Dawson 方道生醫生 (Neurosurgery) Dr HSUE Chan-chee, Victor 徐成之醫生 (Clinical Oncology) Dr KWOK Po-yin, Samuel 郭寶賢醫生 (General Surgery) Dr LAM Siu-keung 林兆強醫生 (Obstetrics & Gynaecology) Dr LAM Wai-man, Wendy 林慧文醫生 (Radiology) Dr LEE Kin-man, Philip 李健民醫生 (Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery) Dr LEE Man-piu, Albert 李文彪醫生 (Dentistry) Dr LI Fuk-him, Dominic 李福謙醫生 (Obstetrics & Gynaecology) Prof LI Ka-wah, Michael, BBS 李家驊醫生 (General Surgery) Dr LO Chor Man 盧礎文醫生 (Emergency Medicine) Dr LO Kwok-wing, Patrick 盧國榮醫生 (Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism) Dr MA Hon-ming, Ernest 馬漢明醫生 (Rehabilitation) Dr MAN Chi-wai 文志衛醫生 (Urology) Dr NG Wah Shan 伍華山醫生 (Emergency Medicine) Dr PANG Chi-wang, Peter 彭志宏醫生 (Plastic Surgery) Dr TSANG Kin-lun 曾建倫醫生 (Neurology) Dr TSANG Wai-kay 曾偉基醫生 (Nephrology) Dr WONG Bun-lap, Bernard 黃品立醫生 (Cardiology) Dr YAU Tsz-kok 游子覺醫生 (Clinical Oncology) Prof YU Chun-ho, Simon 余俊豪教授 (Radiology) Dr YUEN Shi-yin, Nancy 袁淑賢醫生 (Ophthalmology) |

| INTRODUCTION |

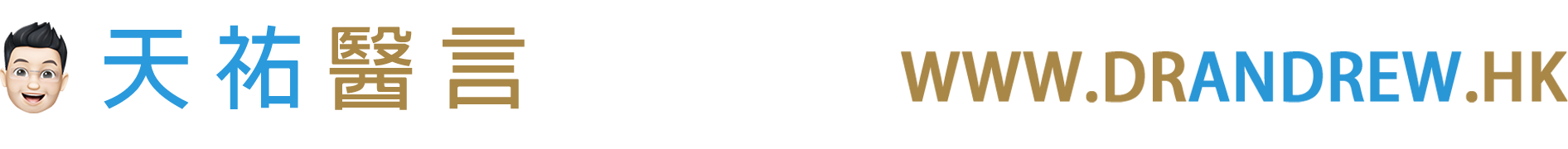

| Human Papillomavirus and Anal Cancer Human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide. HPV is a non-enveloped double-stranded DNA virus that infects mucosal and cutaneous keratinocytes. There are more than 180 subtypes of HPV, of which 40 types infect the anogenital region. These subtypes can usually be categorised into high- vs low-risk in terms of their oncologic potential. Most sexually active males or females will acquire HPV soon after sexual debut. 90% of the infection is silent and will resolve spontaneously1. There are several factors associated with persistent infection, and they are shown in TABLE 12. The longer the duration of an HPV infection, the greater the chance that it will lead to cellular changes. The importance of persistent HPV infection lies in its association with cancer causation. Evidence for cervical cancer has been firmly established3. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is a potential precursor lesion of anal squamous cell carcinoma. Similar to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), AIN is causally linked to persistent infections with high-risk HPV types such as HPV16 or HPV18. There is ample evidence for HPV infection as precursor infection for anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) and anal cancer4. HPV prevalence among patients with AIN is over 90%5. A large metaanalysis found that among patients with cervical, vulvar and anal cancer, those with anal cancer had the highest prevalence of HPV infection (84.3%)6. Furthermore, the amount of HPV DNA is higher in those with high-grade AIN than low-grade AIN, suggesting its biologically plausible role in causing the malignancy7. |

| Patients with AIN are often asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients may present with pruritus or anal discharge. Suspicious lesions may be raised, plaques, scaly, fissured, or eczematous. The colour can be white, erythematous or pigmented23. Patients who describe perianal symptoms consistent with AIN or anal cancer require examination of the perineum, digital rectal examination, and examination of the inguinal area for palpable nodes. When AIN is found, it is important to examine other sites including vulva, vagina and cervix in women and the penis in men, because of the multi-zonal nature of the disease24. The vice-versa should apply to patients detected to have disease involving vulva, vagina and cervix to have a lower threshold of screening for AIN. There is a misconception that anal HPV infection was invariably associated with anal intercourse. In fact, sex does not have to occur for the infection to spread, and most women who have AIN or anal cancer did not have a history of anal intercourse. Skin-to-skin contact with an area of the body infected with HPV is all that is needed for infection to spread. The virus can be spread through genital-to-genital contact or even hand-to-genital contact. HPV infection can also spread from one part of the body to another, for example, from the genitals to anus25. The finding that it is more common in women who clean themselves from front to back after voiding urine is a case in point26. |

| WHY IS DONE? |

| When Pap smear was first introduced to screen for precancerous changes in the cervix of women, it was based theoretically on the pathological progression of precancer changes to cancer. It was after decades of screening that revealed the usefulness of Pap smear in the reduction of cervical cancer. Biological and epidemiological evidence has demonstrated that anal cancer and cervical cancer share lots of analogy and persistent high-risk type HPV infection is even a stronger predictor for anal cancer. Clinical approach to the diagnosis of AIN also borrows from the cervical cancer model and includes the application of colposcopy to the evaluation of anal and perianal region28. The success of cervical cancer screening has led to the use of colposcopy as a template for anal cancer screening in high-risk groups. A retrospective study demonstrated that anal carcinoma developed at previously biopsied sites of high-grade dysplasia in 27 out of 72 anal cancers studied (37.5%), illustrating the potential for the development of anal squamous cell carcinoma from high-grade anal dysplasia29. In this study, nearly half of the HIVinfected MSM with HSIL who developed anal cancer were asymptomatic29. Evidence to support the use of HRA for detection and treatment in the surveillance of AIN exists and strongly suggests that it is beneficial, resulting in reduced rates of cancer progression30. Pilot data demonstrated a 5.72-fold reduction in local disease failure rates of patients with T1-T3 tumours; these data, therefore, suggested that use of HRA for detection and treatment in surveillance of anal cancer patients will help prevent local, regional relapse at the anal site30. Hence the objective of HRA is to detect precancer lesion early. HRA will also allow treatment to be performed to prevent the HSIL from turning into cancer. Anal cytology is only 47 to 70% sensitive in picking up precancerous lesions in HIV-negative MSM31,32. In high-risk population such as HIV-positive MSM, anal cytology can be inaccurate and has been shown not to correlate with histology33. Testing of high-risk human papillomavirus strains 16/18 improves specificity and positive predictive value over cytology for AIN screening. Patients testing positive for strains 16/18 are at high-risk for HSIL and should undergo highresolution anoscopy regardless of the cytology result34. HRA has been recommended by some as a tool for screening in high-risk patients35,36. Apart from a better sensitivity and specificity for picking up abnormal lesions, HRA also allows ablative therapy to be done. However, HRA involves higher demand in terms of expertise and cost. A large retrospective review from 2015 showed that patients followed with standard anoscopy or HRA every 3-12 months had lower rates of progression of AIN to anal cancer, compared to epidemiologic data37,38. Standards and protocols for anal cancer screening are not widely promulgated. The AIDS Institute of the New York State Department of Health has established formal screening guidelines for HIV positive individuals. It recommends routine annual examination of the anus in all HIV-infected adults and cytologic (pap) testing in higher risk HIV-positive patients such as men who have sex with men (MSM), those with a history of genital infection, and women with cervical or vulvar dysplasia39. A colonoscopy does not screen for anal cancer and is not an acceptable alternative to HRA. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) AIDS Info website in 2018 recommended that positive cytology requires follow-up with HRA and that visible lesions should be biopsied. Patients should be referred to expert centres where diagnostic and treatment procedures using HRA can be performed. The high recurrence rates of AIN also warrant ongoing post-treatment surveillance40, 41. For transplant patients, there is a recommendation for annual anal cytology targeting at those with a history of anal intercourse and a history of cervical dysplasia. Abnormal cytology needs a referral to HRA for biopsy and treatment12. |

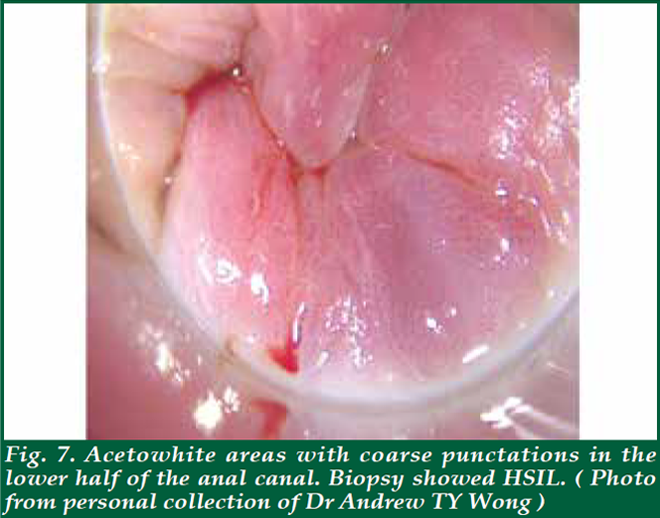

| Before the proper HRA, an anal Pap smear is performed if not done before. Taking an anal pap smear involves gently pushing a fine thin brush into the anal canal to obtain cells from the lining of the anus and collect in liquid medium for cytology. Then, the clinician will examine the anal canal with a finger to feel inside the anus and rectum for abnormal growths and will also examine the skin around the anus for any abnormalities (digital anorectal examination; DARE). As part of DARE, it is important to document any palpable mass lesion, indicating the distance from the anal verge and the proportion of the anal circumference that it occupies. Inspect the glove for blood from the anal canal. For the HRA, a proctoscope will be coated with a lubricant and inserted about two inches into the anus. A cotton swab covered with mild (5%) acetic acid will be inserted through the proctoscope into the anus. Acetic acid is generously and continually applied during the examination to highlight areas of disease. The acetic acid on the cotton swab will cause any abnormal cells to turn white; these are called ‘Acetowhite’ areas. Acetowhite areas/lesions with specific vascular characteristics like punctation or honeycomb patterns are highly suggestive of high-grade disease. (Fig. 7) Lugol’s iodine is then used to highlight Lugol nonuptake areas. With the use of a magnifying colposcope, the clinician performing the examination can detect abnormal areas using the characteristics described above. Should the patients want, they can observe the anoscopy image on the computer screen while the procedure is being performed. After a careful and thorough examination, the doctor will decide whether to take one or more biops(ies) from the anal canal and the perianal area. A local anaesthetic will be injected before the biopsy is taken to help minimise any discomfort. The total time of the procedure is between 20-40 minutes. The procedure is usually very well tolerated with mild, if any, discomfort. Significant risks, such as bleeding or infection, are extremely rare. HRA can also be used to direct therapy. Ablative therapy using infrared coagulation, hyfrecation or laser can be performed during HRA. |

| WHEN IS IT DONE? |

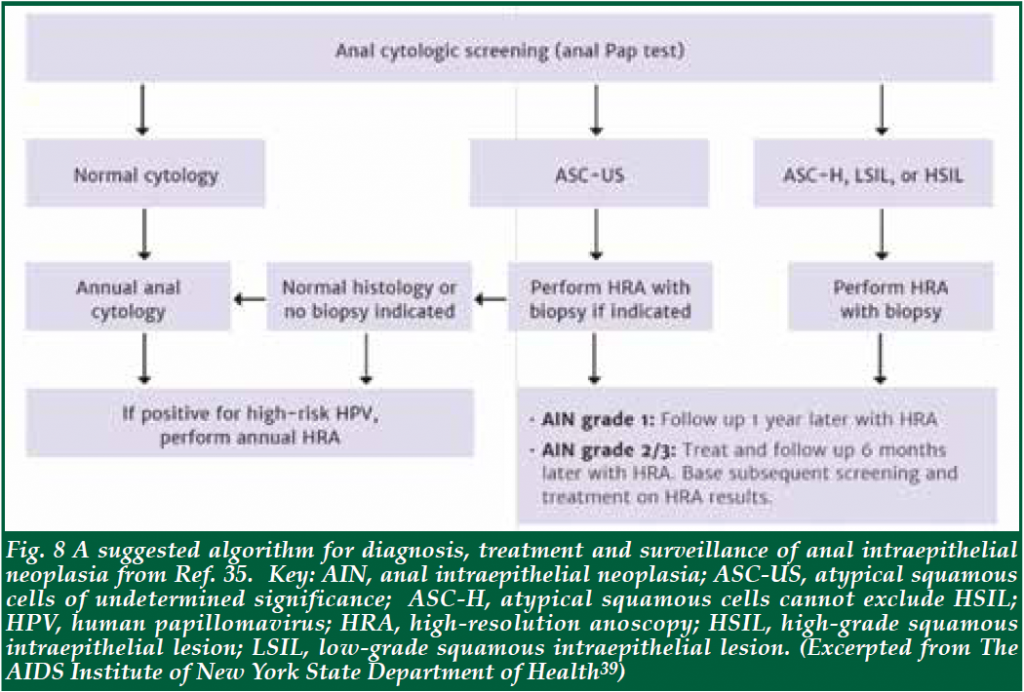

| Screening has been found to be cost-effective for AIN42. Various infectious disease societies have made recommendations for annual cytology for HIV-positive patients, especially those who are MSM, or have a history of cervical cancer43. For timing of subsequent surveillance, there is no established consensus, but most societies recommend yearly surveillance for HIV positive males, and every 3-6 months for those with low- or high-grade AIN44. Fig. 8 showed the recommended algorithm for the diagnosis and management of AIN by Department of Health of New York State, USA35. When high-grade lesions are found, they can be treated either by topical agents or by ablative therapies. The primary topical agents are imiquimod, TCA, and 5-FU. Imiquimod is a synthetic immune modulator that works by upregulating the patient’s immune system to combat the virus. It has been shown to downgrade high-risk lesions to low-risk lesions among HIV-positive patients45. In a randomised study, 61% of patients had an absence of high-risk lesions sustained at 36 months with imiquimod treatment46. The major side effects include treatment area reactions such as irritation and burning pain. TCA has a good safety profile with few major side effects. It can be applied during the examination, and is well-tolerated. Two retrospective studies of small populations of biopsy-confirmed highgrade AIN lesions reported rates of HSIL regressing to LSIL or complete resolution in 71%-79% of cases47,48. 5-FU is a chemotherapy agent that inhibits DNA synthesis and, when applied topically, can clear AIN. Prospective data showed complete clearance of 90%, with a recurrence rate of 50% at 6 months49. Side effects include hypopigmentation or skin irritation. Ablative therapies, including infrared coagulation, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and electrocautery/ hyfrecator are well tolerated. Repeated ablative treatment or a combination of treatment methods are often required for long-term clearance of AIN2-3. Infrared coagulation (IRC) was proven to have moderate efficacy in the treatment of HSIL in patients who are HIV-seropositive in a retrospective study50. It was safe and well-tolerated in the HIV-positive population in a prospective study51. Hyfrecation (electrocautery ablation) is also commonly used to treat anal HSIL. It has a similar efficacy profile to IRC52. Some clinicians prefer it over IRC because it may be faster than IRC, particularly for large and keratotic lesions. It is also easier to use than IRC for the perianal disease. The efficacy of hyfrecation was addressed in a retrospective study in HIV-positive patients where at one-year post-ablation, about 45% of patients developed local recurrence. No patient developed invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA)53. Taken together, topical therapy appears to be generally well-tolerated and offers reasonable efficacy, although a substantial portion of patients will not respond and others will recur. In many centres, topical therapy is utilised as an adjunct to local ablative therapy. At one centre, 248 patients were followed with exams and serial ablative procedures under HRA and supplemental topical treatments. 80% clearance of HSIL was demonstrated and only 1.2% of the patients developed anal cancer54. Currently, a prospective randomised study called Anal Cancer HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) to determine whether screening and treatment of HSIL are effective in reducing subsequent anal cancer in HIV-positive men and women compared with active monitoring via regular exams (including anal cytology combined with HRA and biopsy of any concerning lesions) vs observation is underway in 12 sites in the United States. Treatments can include imiquimod, fluorouracil, electrocautery, and laser therapy. The study will be able to answer questions like the best strategy for AIN surveillance and the efficacy and safety of different treatment modalities55. |

| WHO ARE THE AT RISK GROUP? |

| Anal cancer is uncommon, with an incidence rate of around 2 per 100,000 of the general population8,10, but incidence rates have been steadily increasing over the last three decades9. It is more common in females than in males9. Anal cancer is increasing significantly among some groups of people13, especially those infected with HIV, men who have sex with men (MSM)10, women with a history of cervical, vaginal or vulvar cancer11, tobacco smokers, and people who are immunocompromised due to organ transplants12, steroid use, or the use of any medications that suppress the immune system. In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected MSM, anal HPV prevalence is more than 90%, and infections with multiple HPV types are common14. Consequently, HPV-associated anogenital malignancies occur with high frequency in patients with HIV infection. Although anal cancer is not an AIDS-defining cancer, it is 30- 100 times more common in HIV-positive individuals15. Studies have indicated that a low CD4 count in HIVpositive individuals is a risk factor for AIN and invasive anal cancer16. |

| WHAT IS ANAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASI A AND HOW TO RECOGNISE IT? |

| Anal squamous dysplasia refers to a spectrum of disease ranging from low-grade intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) to high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) to invasive anal squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA). They can involve both the perianal skin and anal canal. ‘Intraepithelial’ in anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) refers to the abnormal cells not having gone further than the epithelium or the lining of the anus. AIN can either be LSIL or HSIL17. Inside the anal canal, the histopathologic manifestations of HPV infection are most commonly detected at the anal transition zone (ATZ), where the rectal columnar epithelium and anal squamous epithelium meet (known as the squamo-columnar junction, SCJ)18,19 (Fig. 1) The anus and cervix also share embryological origins and susceptibility to HPV infection, which might also explain the similarities between these malignancies. LSIL usually goes away on its own, without treatment. But some of them associated with an increased risk of HSIL are less likely to go away on their own, with approximately one in ten chance of becoming a VOL.25 NO.8 AUGUST 2020 Medical Bulletin 17 cancer over approximately five years20,21. But there is heterogeneity, and the rate is highest in highrisk populations. The rate of progression of AIN to invasive anal cancer more closely resembles the natural history of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia, with expected malignant transformation in about 10% of immunocompetent patients over five years22. |

| WHAT IS High-resolution Anoscopy? |

| High-resolution anoscopy, or HRA, is a procedure that allows for examination of the anal canal and surrounding skin using a colposcope. The 10-40 times magnifying power of the colposcope allows for the direct visualisation of the mucosal surface of the anal canal and the surrounding skin of the perianal area. In addition, staining up with acetic acid and Lugol’s iodine will enable lesions which are otherwise invisible to the naked eyes to be picked up for biopsy for confirmation of histology. HRA is well known for its steep learning curve, and hence quality assurance is of vital importance in ensuring proper care. For that, the International Anal Neoplasia Society (IANS) has defined minimum standards for service to guide HRA practitioners on the set-up and implementation of high-resolution anoscopy, the provision of information to patients, staffing, infection control, medical notes, and follow up referrals to and communication with a team of specialists27. |

| WHO SHOULD HAVE HRA? |

| • People who have a higher risk of developing anal cancer. They includes both men and women who are immunosuppressed; this could be due to HIV infection, organ transplants, long term steroid use or other medicine that suppresses immune function, or any other condition that affects the immune system. • People who have a history of anal dysplasia (precancerous changes) or cervical or vulval dysplasia (women). |

| HOW IS IT DONE? |

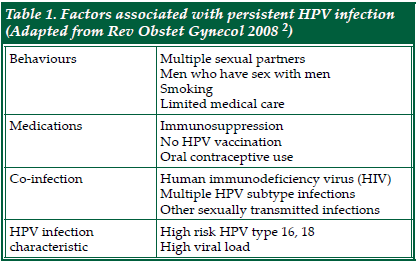

| There is no special preparation needed for the assessment. The procedure is performed on an outpatient basis. Starting 24 hours before the examination, avoid using any douches, enemas or creams that are applied to the anal canal. It is also important to avoid anal sex. The patient will be asked to remove the lower half of his/her clothes and given a gown opening at the back. There are several positions for performing HRA. In the UK, it is done in a lithotomy position (Fig. 2). In the Netherlands, it is performed in lithotomy position too, but the legs are elevated much higher than those in UK (Fig. 3). In USA, it is either performed in kneechest position (Fig. 4) or lateral position. In Australia, it is performed in a lateral position (Fig. 5). Some patients may prefer lateral position as they claim to be less vulnerable in that position. The choice of the position depends on the habits and practice of the operators as well. Personally, I find the lithotomy (especially with the end of the pelvic table tilted up considerably) or kneechest position can expose the SCJ better as the mucosal folds tend to gravitate towards the colon end and provide a better view. Knee chest position can be challenging for some patients who have knee problems. Hence, I adopt the lithotomy position in Hong Kong (Fig. 6). |

| ROLE OF HPV VACCINATION |

| HPV vaccine is currently recommended only as a preventive immunisation for youth between the ages of 9 to 26. US CDC recommends it for people of all gender identities and sexual orientations, starting at age 11 or 12. Since it is intended to be given before sexual activity begins, it can be given as early as nine years of age. ACIP also recommends vaccination through age 26 years for those who were not adequately vaccinated previously, including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, transgender people, and immunocompromised persons (including those with HIV infection)56. A trial using quadrivalent vaccines among MSM showed that the incidence of anal SIL associated with HPV 6, 11, 16, or 18 was decreased by 78% and the incidence of persistent HPV infection of relevant types was decreased by 95% in those receiving the vaccine compared with those receiving placebo (per protocol efficacy). 165 (27.4%) men were seropositive or HPV DNA–positive for HPV-6 or 11, 99 (16.4%) for HPV16, and 68 (11.3%) for HPV-18. Hence HPV vaccine is useful for prevention of AIN and should preferably be given before sexual activity begins57. Administration of the vaccine after the diagnosis of Administration of the vaccine after the diagnosis of AIN in order to assist with prevention in the future has been studied. Retrospective data showed that vaccination could lower the rates of HSIL in MSM with recurrent AIN58. A randomised trial involving MSM found the rates of AIN were lower in the vaccine group, while they also had a significantly lower risk for persistent HPV infection following vaccination59. Therefore, patients with AIN may benefit from the vaccine though it is considered an off-label use of the vaccine. |

| FINAL REMARKS |

| HRA of the anal region, analogous to colposcopy of the cervix, is a technique that is not well-known in the medical and surgical fraternity. There is much potential room for improvement in general knowledge about the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of chronic HPV infection, AIN and anal cancer among medical practitioners and patients in high-risk groups alike. Specialists taking care of high-risk patients need to be aware of this disease entity and educate patients about the disease and prevention methods. This applies especially to gynaecologists and oncologists taking care of patients with other HPV-associated cancers; nephrologists or transplant physicians taking care of transplant patients ;and rheumatologists and other physicians taking care of patients on immunosuppressants. To facilitate communication and better understand risks, healthcare providers need to learn how to comfortably take a proper sexual history in a non judgemental way, regardless of stated or assumed sexual orientation, to better understand who is at risk. In patients with AIN or SCCA, Smoking cessation should be encouraged. Women should be made aware that anal HPV recovery does not mean anal intercourse and should be encouraged to abolish shame associated with the condition and come forwards to seek medical help if they notice any anal symptoms. There is a high correlation between cervical and anal cancer risk in women. For MSM, due to the high rate of sexually transmitted diseases and anal cancer among this population, a comprehensive STDs screening and prevention strategy inclusive for HPV should be in place. |

- References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease

- Surveillance 2015. Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2015. Atlanta: US

- Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

- Dempsey AF. Human papillomavirus: the usefulness of risk factors in

- determining who should get vaccinated. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2008;1:122-128.

- Crosbie EJ, Einstein MH, Franceschi S, Kitchener HC. Human

- papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2013;382:889-899.

- Shah KV. Human papillomaviruses and anogenital cancers. N Engl J Med

- 1997; 337: 1386-1388 [PMID: 9358136 DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371911]

- Bosch FX, Broker TR, Forman D, et al. authors of ICO Monograph

- Comprehensive Control of HPV Infections and Related Diseases Vaccine

- Volume 30, Supplement 5, 2012. Comprehensive control of human

- papillomavirus infections and related diseases. Vaccine. 2013;31(Suppl

- 7):H1–H31.

- De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S.

- Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma

- and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis.

- Int J Cancer 2009;124:1626-1636.

- Salit IE, Tinmouth J, Chong S, et al. Screening for HIV-associated anal

- cancer: correlation of HPV genotypes, p16, and E6 transcripts with anal

- pathology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:1986-1992.

- SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Anal Cancer. National Cancer Institute.

- Available from: URL: http//seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/anus.html

- Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Machalek DA, et al. The epidemiology of anal

- cancer. Sex Health 2012;9:504–8.

- Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, Engels E, Gill MJ, Goedert JJ, Kirk GD,

- D’Souza G, Bosch RJ, Brooks JT, Napravnik S, Hessol NA, Jacobson LP,

- Kitahata MM, Klein MB, Moore RD, Rodriguez B, Rourke SB, Saag MS,

- Sterling TR, Gebo KA, Press N, Martin JN, Dubrow R. Risk of anal cancer in

- HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin Infect

- Dis 2012; 54: 1026-1034 [PMID: 22291097 DOI: 10.1093/cid/cir1012]

- Lin C et al. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the

- anus: according to sex and HIV status: a systematic review and metaanalysis.

- Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:198-206.

- Chin-Hong PV & Reid GE on behalf of AST Infectious Diseases Community

- of Practice. Human Papilloma Virus Infection in solid organ transplant

- recipients: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation

- Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clinical Transplantation 2019:00:

- e13590

- Roberts JR et al. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia: A review of diagnosis and

- management. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9: 50-61.

- Park IU, Palefsky JM. Evaluation and management of anal intraepithelial

- neoplasia in HIV-negative and HIV-positive men who have sex with men.

- Curr Infect Dis Rep 2010;12:126-133.

- Wasserman P, Rubin DS, Turett G. Review: Anal intraepithelial neoplasia

- in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: is screening and treatment

- justified? AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:245-253.

- Nancy F. Crum-Cianflone et al. Anal Cancers among HIV-Infected

- Persons: HAART Is Not Slowing Rising Incidence. AIDS. 2010; 24: 535–543.

- doi:10.1097.

- Darragh TM et al. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology

- Standardization Project for HPV-Associated Lesions: Background and

- Consensus Recommendations from the College of American Pathologists

- and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Archives

- of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2012 136:10, 1266-1297.

- Alemany L, Saunier M, Alvarado-Cabrero I, et al. Human papillomavirus

- DNA prevalence and type distribution in anal carcinomas worldwide. Int J

- Cancer. 2015;136(1):98‐107. doi:10.1002/ijc.28963

- Palefsky M. Anal human papillomavirus infection and anal cancer in HIVpositive

- individuals: an emerging problem. AIDS. 1994;8:283.

- Scholefield JH, Castle MT, Watson NF. Malignant transformation of highgrade

- anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Surg 2005;92:1133-1136.

- Watson AJ, Smith BB, Whitehead MR, Sykes PH, Frizelle FA. Malignant

- progression of anal intra-epithelial neoplasia. ANZ J Surg 2006;76:715-717.

- Scholefield JH, Harris D, Radcliffe A. Guidelines for management of anal

- intraepithelial neoplasia. Colorectal Dis 2011;13(suppl 1):3-10.

- Zbar AP, Fenger C, Efron J, Beer-Gabel M, Wexner SD. The pathology

- and molecular biology of anal intraepithelial neoplasia: comparisons

- with cervical and vulvar intraepithelial carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis

- 2002;17:203-15.

- Carter JJ, Madeleine MM, Shera K, Schwartz SM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wipf

- GC, et al.Human papillomavirus 16 and 18 L1 serology compared across

- anogenital cancer sites. Cancer Res 2001;61:1934-40.

- American Cancer Society. Risk Factors for Anal Cancer. Assessed from

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/anal-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/riskfactors.

- html

- Simpson S et al. Front-to-back & dabbing wiping behaviour post-toilet

- associated with anal neoplasia & HR-HPV carriage in women with previous

- HPV-mediated gynaecological neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol 2016; 42:124-

- 132.

- Hillman RJ et al. 2016 IANS International Guidelines for Practice Standards

- in the Detection of Anal Cancer Precursors. Journal of Lower Genital Tract

- Dis 2016; 20: 283-291.

- Darragh TM, Winkler B. Anal cancer and cervical cancer screening: key

- differences. Cancer Cytopathol 2011;119(01):5–19.

- Berry JM, Jay N, Cranston RD, et al. Progression of anal high-grade

- squamous intraepithelial lesions to invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected

- men who have sex with men. Int J Cancer 2014;134:1147–1155.

- Goon P et al. High resolution anoscopy may be useful in achieving

- reductions in anal cancer local disease failure rates: HRA may prevent

- anal cancer local disease failure. European journal of cancer care. 2013; 24.

- 10.1111/ecc.12168.

- Nathan M, Singh N, Garrett N, Hickey N, Prevost T, Sheaff M. Performance

- of anal cytology in a clinical setting when measured against histology and

- high-resolution anoscopy findings. AIDS 2010; 24: 373-379.

- Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Hogeboom CJ, Berry JM, Jay N, Darragh TM. Anal

- cytology as a screening tool for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. J

- Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1997; 14: 415-422.

- Panther LA, Wagner K, Proper J, et al. High resolution anoscopy findings

- for men who have sex with men: inaccuracy of anal cytology as a predictor

- of histologic high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia and the impact of HIV

- serostatus. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38(10):1490–1492.

- Sambursky JA, Terlizzi JP, Goldstone SE. Testing for Human Papillomavirus

- Strains 16 and 18 Helps Predict the Presence of Anal High-Grade Squamous

- Intraepithelial Lesions. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1364-1371. doi:10.1097/

- DCR.0000000000001143

- Nahas CS, de Silvia Filho EV, Segurado AA, et al. Screening anal dysplasia

- in HIV-infected patients: is there an agreement between anal pap smear and

- high-resolution anoscopy-guided biopsy? Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1854-

- 1860.

- Shridhar, R., Shibata, D., Chan, E., Thomas, C. Anal Cancer: Current

Standards in Care and Recent Changes in Practice. CA: A Cancer Journal for

Clinicians 2015; 65:139-162. doi.org/10.3322/caac.21259 - Long KC, Menon R, Bastawrous A, Billingham R. Screening, surveillance,

and treatment of anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Colon Rectal Surg

2016;29:57-64. - Crawshaw BP, Russ AJ, Stein SL, et al. High-resolution anoscopy or

expectant management for anal intraepithelial neoplasia for the prevention

of anal cancer: is there really a difference? Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58:53-59. - The AIDS Institute of New York State Department of Health. Screening for

Anal Dysplasia and Cancer in Patients with HIV. Assessed at https://www.

hivguidelines.org/hiv-care/anal-dysplasia-cancer/#tab_3 - US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the Prevention

and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with

HIV. Section on Human Papilloma Virus at AIDSInfo https://aidsinfo.nih.

gov/guidelines/html/4/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection/343/

human-papillomavirus-disease assessed on 1 Jun 2020. - Dalla Pria A, Alfa-Wali M, Fox P, et al. High-resolution anoscopy screening

of HIV-positive MSM: longitudinal results from a pilot study. AIDS

2014;28:861-867. - Goldie SJ, Kuntz KM, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA, Palefsky JM. Costeffectiveness

of screening for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and

anal cancer in human immunodeficiency virus-negative homosexual and

bisexual men. Am J Med 2000;108:634-641. - Dindo D, Nocito A, Schettle M, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D. What should we

do about anal condyloma and anal intraepithelial neoplasia? Results of a

survey. Colorectal Dis 2011;13:796-801. - Siddharthana RV, Lanciaultb C, Tsikitis VL. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia:

diagnosis, screening, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol 2019; 32: 1-7. - Wieland U, Brockmeyer NH, Weissenborn SJ, et al. Imiquimod treatment

of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive men. Arch Dermatol

2006;142:1438-1444. - Fox PA, Nathan M, Francis N, et al. A double-blind, randomized controlled

trial of the use of imiquimod cream for the treatment of anal canal highgrade

anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive MSM on HAART, with

long-term follow-up data including the use of open-label imiquimod. AIDS

2010; 24:2331-2335. - Cranston RD, Baker JR, Liu Y, Wang L, Elishaev E, Ho KS. Topical

application of trichloroacetic acid is efficacious for the treatment of internal

anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-positive men. Sex

Transm Dis 2014; 41: 420-426. - Singh JC, Kuohung V, Palefsky JM. Efficacy of trichloroacetic acid in the

treatment of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive and HIV-negative

men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52: 474-

479 . - Richel O, Wieland U, de Vries HJ, et al. Topical 5-fluorouracil treatment of

anal intraepithelial neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-positive

men. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:1301-1307. - Goldstone SE, Kawalek AZ, Huyett JW. Infrared coagulator: a useful

tool for treating anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. Dis Colon

Rectum. 2005;48(5):1042-1054. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/15868241 - Stier EA, Goldstone SE, Berry JM, et al. Infrared coagulator treatment of

high grade anal dysplasia in HIV-infected individuals: an AIDS malignancy

consortium pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:56-61. - Marks DK, Goldstone SE Electrocautery ablation of high-grade anal

squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-negative and HIV-positive men

who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Mar;59 :259-65. - Gaisa MM, Liu Y, Deshmukh AA, Stone KL, Sigel KM.Electrocautery

ablation of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: Effectiveness

and key factors associated with outcomes. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1470. Epub

2020 Jan 24. - Pineda CE, Berry JM, Jay N, Palefsky JM, Welton ML. High-resolution

anoscopy targeted surgical destruction of anal high-grade squamous

intraepithelial lesions: a ten-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:829-

835. - SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Anal Cancer. National Cancer Institute.

Bethesda, MD. Available from: URL: http//anchorstudy. org/about - US CDC HPV Vaccine Recommendations accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/

vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html - Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV

infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1576. - Swedish KA, Factor SH, Goldstone SE. Prevention of recurrent highgrade

anal neoplasia with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination of men

who have sex with men: a nonconcurrent cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2012;

54:891-8. - Vaccine therapy in preventing Human papillomavirus infection in young

HIV-positive male patients who have sex with males. In: ClinicalTrials.

gov [Internet]. Available from: https:// clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/

NCT01209325?term=NCT01209325 NLM Identifier: NCT01209325. - Lin C et al. Cervical determinants of anal HPV infection and high-grade anal

lesions in women: a collaborative pooled analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:

880-891.

Forward from《The Hong Kong Medical Diary》